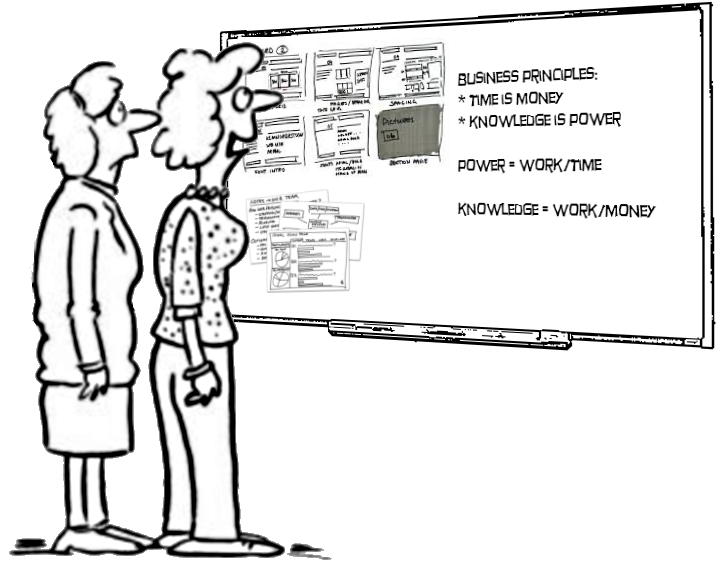

That query also reminded me of a rather old humorous anecdote that describes a conversation between a manager and an engineer. As the manager boasts about their latest purchase, the engineer points out that salary is an inversely relational function of knowledge. The engineer explains while writing on the whiteboard in her office...

Two common business principles are that time is money and knowledge is power, and we know that a physical law of the universe is that power multiplied by time is work. It follows, then, knowledge multiplied by money is work - which, of course, means that that knowledge is work divided by money. This means that as knowledge approaches infinity, money approaches zero - as well as the inverse - as money approaches infinity, knowledge approaches zero.

Of course one might argue that the engineer's equations only work if we use these idiomatic expressions and rely on the connotations of the words within them rather than the denotations (as the sciences are wont to do). Regardless, once again, we have used humor to shine a light on an uncomfortable truth - thinking is seldom valued in a world where the "bottom line" is monetary.

We - especially Americans - want to believe we live in a knowledge-based meritocracy. We've been sold on a "knowledge economy" and have been told that we trade time and knowledge for money; however, that's not really true, because in reality, knowledge is not power.

So, where did we get this idea that knowledge is power?

The phrase "scientia potentia est" or "knowledge is power" enters the vernacular around the middle of the 17th century - first through Sir Francis Bacon's writing about God Note 1 and about 50 years later through Thomas Hobbes Note 2.

It is interesting to note that prior to Bacon and Hobbes the most common expressions were not about knowledge being power, but wisdom Note 3. Much has been made of the difference between knowledge and wisdom, and frankly, it is unlikely that the distinction would alter the meaning much - or at least not as much as the connection between knowledge and action that Bacon and Hobbes emphasize.

By now you're probably wondering what all this has to do with getting paid to think. We, as a society, have been trained by business models that knowledge and thinking are separate from doing - but the thing is, they aren't. Knowledge is, to paraphrase great thinkers, potential and thinking makes that potential actual. Until we all recognize that, we will be left with the sad reality that is revealed in the engineer's equations.

Notes and references

Links in the notes and references list open in a new window- "...vel putius ejus partis potestatis Dei, (nam et ipsa scientia potestas est) qua scit, quam ejus qua raovet et agit..." or "...rather to that part of God’s power (for knowledge itself is power) whereby he knows, than to that whereby he works and acts..." ~ Sir Francis Bacon, Meditationes Sacrae, 1597. It's worth noting, by the way, that Bacon was talking about God's knowledge, not knowledge in general, and that the knowledge is tied directly to action - knowing is doing.

- "The sciences are small powers" or "scientia potentia est, sed parva" ~ Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, 1651. It's worth noting that, like Bacon, Hobbes ties knowledge (or "sciences") directly to action - making it especially clear in De Corpore a short 4 years later when he says "the scope of all speculation is the performing of some action".

- Two such examples are from the latter half of the Mishlei Shlomo (Proverbs of Solomon), from a section referred to as "the sayings of the wise", where it says "a wise man is powerful" and the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), where it says "one who has wisdom is powerful".

No comments:

Post a Comment